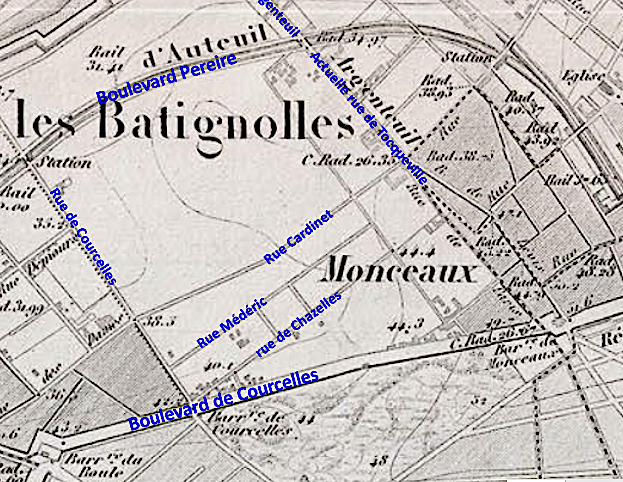

Under the Ancien Régime, the present-day Plaine Monceau served as a key hunting ground. In 1791, exasperated by the damage to their crops caused by animals escaping from the game preserves, the local inhabitants destroyed these preserves, which symbolized the inequalities of the Ancien Régime. During the French Revolution, the area remained sparsely populated, with only 450 residents. A 1780 land registry of Clichy recorded place names such as Sainte-Catherine, Les Terres Rondes, Les Fosselles, and La Terrasse, which also appear on cadastral maps from the early 19th century. However, an ambitious development plan for Plaine Monceau proposed in 1837 failed to materialize, leaving the area predominantly rural until 1854, when the Pereire Boulevard—named after the Pereire brothers—became the first major thoroughfare, linked to the construction of the Auteuil railway line.

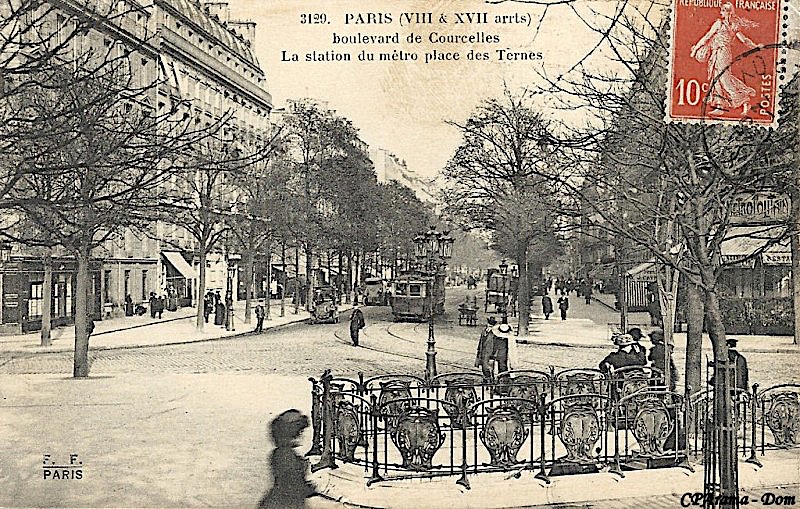

At that time, the Monceau district remained largely agricultural, with minimal construction. It was bounded by the fortified wall built between 1841 and 1843 to the north, the road to Asnières (now Rue de Tocqueville) to the east, the outer boulevard of the Farmers-General wall (now Boulevard de Courcelles) to the south, and Rue de Courcelles to the west. North of Rue Cardinet, the area contained few roads, with only a handful of winding rural paths. However, settlements began to emerge on its fringes. By 1825, the Batignolles district had developed to the southeast, while to the southwest, around Rue de Lévis, the former hamlet of Monceaux also grew. Together, these settlements formed the commune of Batignolles-Monceaux in 1830, after separating from Clichy. Its population surged from 7,014 in 1831 to 44,094 in 1856.

In 1853, the Batignolles-Monceaux commune offered a strip of land along the fortifications between Rue de Saussure and Porte Maillot to the Pereire brothers’ railway company. In return, the company agreed to construct a ten-meter-wide boulevard on each side of the railway and build a station at the Cardinet bridge. The resulting Auteuil line, designed for urban passenger service, became a precursor to the modern metro and catalyzed the district’s urbanization. Speculators, anticipating development, had already begun purchasing land to create reserves for future expansion.

From the late 1850s, urbanization accelerated under Haussmann's leadership in collaboration with Émile Pereire, one of the district’s primary landowners. Before its annexation to Paris in 1860, Batignolles-Monceaux was the least developed of the suburban areas incorporated by the city. Following the Pereire Boulevard (established in 1854), major thoroughfares such as Avenue de Wagram, Boulevard Malesherbes, and Avenue de Villiers were opened between 1859 and 1860. Additional streets, including Rue Jouffroy (1862), Rue Ampère, Rue de Prony, Rue de Romme (north), Rue Brémontier, and Rue Alphonse-de-Neuville, as well as Avenues Niel and Gourgaud (1866), were completed during the Second Empire. By 1869, the northern section of Boulevard Pereire and the southern section of Rue de Rome had been constructed. Secondary roads followed between 1872 and 1887. To ensure rapid development, the Pereire brothers sold parcels of land, often imposing strict conditions, such as requiring buyers to build bourgeois homes within six months, discouraging speculative holding.

The Plaine Monceau was largely built on subdivided plots during the final third of the 19th century. Roads, wider than the Parisian average, were laid out independently of earlier networks, contributing to the district’s homogeneity and architectural cohesion. Unlike other areas of Paris, modern buildings from the 20th century are rare and, when present, are carefully integrated into the historic streetscape or confined to the periphery (north of Boulevard Berthier, in the former “Zone”).

Haussmann’s vision of Plaine Monceau as a residential neighborhood for the upper bourgeoisie remains intact. Shops and services are limited to key intersections, and the area lacks a central commercial hub. During the late Second Empire, Haussmann-style apartment buildings emerged along major thoroughfares, but between the 1860s and 1880s, private mansions were the dominant architectural style. These mansions, modest in size (6 to 10 meters wide), were typically built with courtyards or rear gardens. During the peak urbanization period (1875–1895), construction companies, such as the Compagnie des Immeubles de la Plaine-Monceau and various insurance firms, developed cohesive blocks of apartment buildings along newly created streets. Nonetheless, private mansions continued to be built into the early 20th century, particularly along Rue de Prony and adjacent streets.

In this evolving urban and real estate context of a “new city,” the Sofia parish acquired land on Rue Médéric to build a new church—the one that stands today.